These ideas are essential pillars of reader-response theory, which argues that meaning is present intrinsically in a work, but is rather created by the reader's response. (Go figure.) And, extending this, it may be found that, whether intentionally or not, many authors manipulate a reader's response to have a certain emotional effect or convey a certain theme.

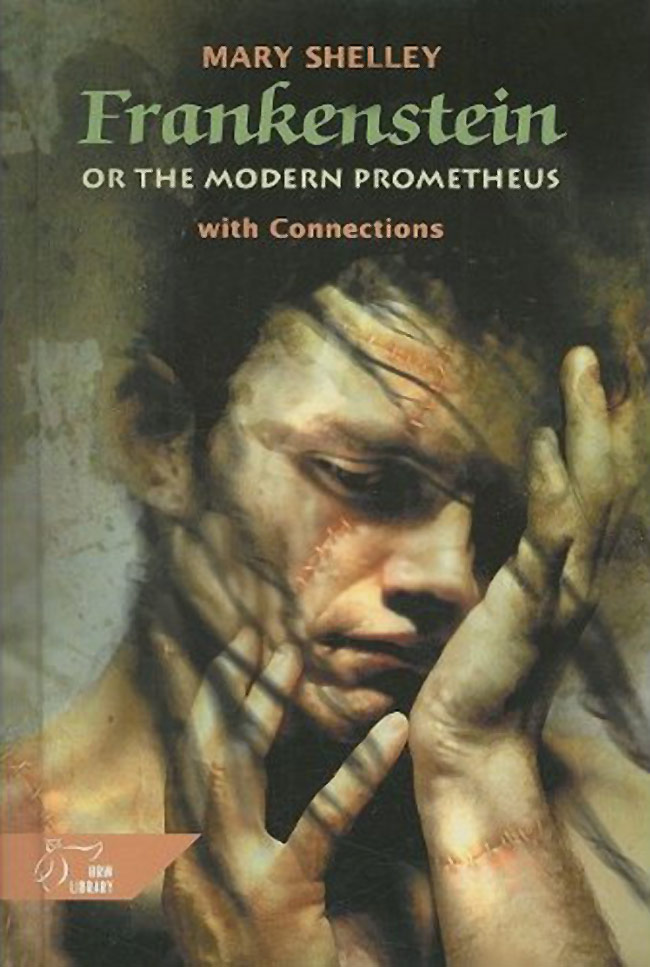

Reader response theory has many interesting models within it, any one of which could take up a blog post of their own, but right now I want to focus on how the theory as a whole applies to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

This book begins with a frame story from the point of view of Robert Walton, a young man who seeks to explore the Arctic. I found him to be a very sympathetic character; his responses to the various events in the plot seem natural and his curiosity and ambition genuine. Perhaps Shelley intended us to identify with this character, and thus to consider the events in the story as if they are occurring to us.

As the book transferred perspectives, I found that the responses of everyone in our class diverged somewhat. I personally sympathized with Frankenstein considerably throughout the novel; while he made many mistakes and bad decisions, and never seemed to realize that he was entirely responsible for the creature's downfall, his intentions remained good throughout. Others in the class focused more on his mistakes and the creature's blamelessness, and perceived Frankenstein as being closer to a villain.

Differences in perception also appeared to influence the themes that each of us saw in the book. Common themes included the dangers of scientific development without consideration for ethics and the responsibility that a creator holds towards the creation, both of which are more easily seen if the reader views Frankenstein in a negative light. It seems quite possible that Shelley deliberately portrayed Frankenstein in this way, introducing unrealistic mistakes and actions, to highlight those themes which she wished readers to take away from the work.