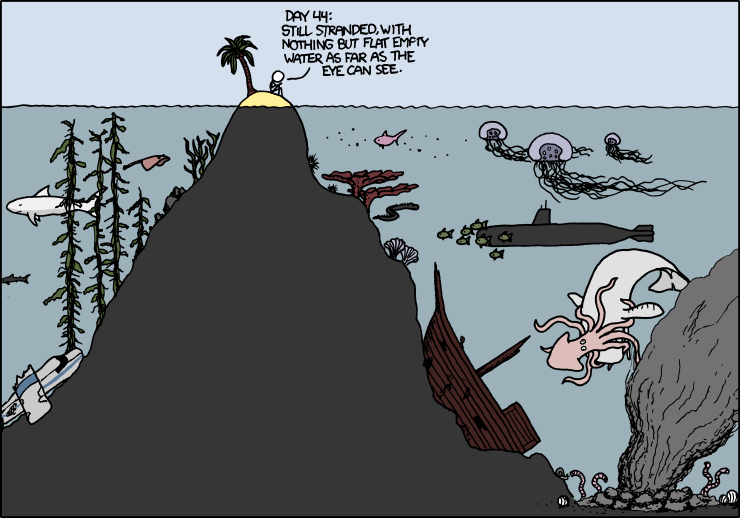

[ Obscure reference? ] [ Obscure reference. ]

In class, we discussed a few things: most chiefly, at least in my memory, was annotation and strategies for understanding and recalling details.

I have had a long and tumultuous love-and-hate affair with annotation and other strategies. In middle school, I was forced to do Cornell notes, and worse, they were structured the wrong way. So began my epic distrust of notation strategies. After all, Gandalf didn't need notes to know everything, so why would I?

The fact that fictional wizards can do pretty much

whatever they want was conveniently overlooked by my young mind.

Later, I began to discover that outline notes were easy to do and organized the material nicely, and happily wrote such notes for the month leading up to the first AP World History test. However, there was a slight issue; I'm chiefly a skimmer, and rarely read word by word unless I'm analyzing the quality of the text or know that the writer will make it worth my time. (Bradbury, I'm looking at you!)

This did result in some difficulties paying attention when I tried to study my notes directly, though. After dozing through about an hour of "study" time, I ended up just reading the textbook over again.

I did just fine on the test.

This strategy first began to fail me in my AP English class last year. Mrs. Turner's monumentally difficult quizzes broke through my refusal to take notes in fewer than three class periods, and I dutifully took Cornell notes for the remainder of the course (though with a certain twist-- I didn't write down questions or a summary, but shorter and shorter outlines of the notes). I do remember much of the material to this day.

Which brings me to an interesting question. What made that note-taking strategy so much more effective for me? Why could I take Cornell notes and use those to study, while plain outline notes put me to sleep? Did something about the format help my mind understand the concepts?

What is understanding, anyway? Remembering things? Computer programs can do that easily, but they can't synthesize concepts into new information.

To answer this question, we may have to draw on our old friend the dictionary. The direct definition probably won't do us much good, but the older roots of the word might. Words are a little bit like equations to me-- they're hard to figure out when they're whole, but if we break them up into pieces, they become more manageable. (Sometimes, anyway.)

Under-stand, from the Proto-Germanic *under ("between") and *standana ("to stand"). [Wiktionary]

So, understanding means to stand between? Or, maybe, to stand within a concept? Not terribly useful to us; words often change in meaning so much that it's hard to glean any insight.

What about a modern language instead? Spanish doesn't do us much good either-- entender? A verb from the Latin

intendere, but Latin never tells me anything about nuances.

Let's try Korean.

The most basic word for understanding that I know is 이해 (

ihae). I'm not nearly good enough to decipher the etymology, though (it's from these scary Chinese characters) so maybe 알아들어 (

araduro) is better? From my understanding, when used in a sentence, it means something close to understanding or learning; literally, it means "know-hear" or "learn-hear".

Hearing and learning-- or, in my case, reading and learning-- means something a little different from standing within things.

So as a composite definition, maybe understanding is listening or reading carefully, learning the concepts, and trying to look at them from all sides until you know them.

So where do notes come in? Well, the concept behind Cornell notes is that the reinforcement of material multiple times, each time in a further-compressed format, will help to drive facts firmly into your brain. But does this really help understanding?

Well, maybe.

As it turns out, whenever I take Cornell notes, I end up compressing them into shorter and shorter versions in the various spaces on the sheet each time I look at them. I simply can't passively read things, especially my own notes, just as I can't listen in class without reading a passage, answering questions, or doing something with my hands at the same time. (With that in mind, Mr. Mullins, I swear that I'm paying attention in class even if I'm fooling with a piece of paper or something! I fall asleep if I sit still!)

And when I compress my Cornell notes, I am forced to make connections between facts even as they're hammered into my brain. When writing down each art piece from the Northern Renaissance, I recall the details that I saw in the book, and make comparisons between pieces. When writing down things that popped out at me from the Paris Review interviews and briefly looked at them later, I noticed similarities and differences between authors. In this way, I ended up with a better understanding of the material than if I had written "normal" outline or Cornell notes.

So perhaps writing notes in the ways that I've found, even if they're not perfectly orthodox, helps me "stand inside" the material in a way that just reading the material or annotating the text doesn't.

Or maybe I'm making this far too complicated. After all, Gandalf didn't need etymology to know everything. I've found a system of notes that works, and that's good enough for me.

But even Gandalf needed a little upgrade, in the form of new robes. I'm not ready to declare that grey is the best color-- maybe I just haven't seen white yet.

,_ENT.jpg)

.png)